Washi = Japanese Paper

Papermaking was introduced to Japan more than 1,300 years ago. The Chronicles of Japan, Nihon Shoki, written in the year 720, state that the Chinese methods of making ink and paper were introduced to Japan by the Korean Buddhist priest, Doncho, in 610. The Prince Regent Shotoku found Chinese paper too fragile and encouraged the use of kozo (mulberry) and hemp fibers, which were already cultivated for use in making textiles.

The techniques of making paper spread throughout the country and under his patronage, the original process slowly evolved into the Nagashizuki method of making paper, using kozoand neri (a viscous formation aid that suspends fibers evenly in water). These skills have been passed down from generation to generation, producing a paper that was not only functional, but reflecting the soul and spirit of the maker. The close relationships between the papermaker and his paper and then paper to paper user resulted in washi becoming an integral part of Japanese culture.

Traditionally, the making of washi was a seasonal process. Most of the papermakers were farmers who planted kozo and hemp in addition to their regular crops. The best washi was made during the cold winter months. This coincided with the season when the farmers could not work in their fields and the ice water was free of impurities, which if present could discolor the fibers.

During the Meiji period (mid-19th Century) the demand for paper greatly increased. However, the Meiji period was the beginning of the shift from washi to western paper and from handmade to machine-made papers. Despite the change in demand, the strong yet flexible washi is still a large facet of Japanese culture; it is still used for special religious purposes (both Buddhist and Shinto), in the production of daily items like toys, fans, and garments, as well as for conservation purposes and washi’s most universally recognized function, traditional architecture.

As new uses for paper are being discovered and tested, so too must washi evolve while the papermakers uphold their traditional skills. Thanks to the gravitation of artists, conservators, enthusiasts, and craftspeople to the strength, flexibility, and beauty of washi, Japanese papers are becoming relevant once more. Washi is now on display in exhibitions, installations, discussions, and architecture throughout the world making it increasingly accessible and inspirational for those who have not yet witnessed its remarkable potential.

Kozo

(Mulberry)Kozo (Mulberry) bark is used in approximately 90% of the washi made today. Kozo was originally found in the mountain wilderness of Shikoku and Kyushu Islands. It became a cultivated plant used especially for paper and cloth making. It is a deciduous shrub that grows to a height of 3 - 5 meters with the stem measuring up to 10cm across.

Gampi

A bush found in the mountainous, warm areas of Japan. Gampi grows to 1.0 - 1.5 meters in height. It has been used as a washi-making material for many years due to the high quality of the fiber taken from the bark.The finished paper is somewhat translucent and has a shiny texture. Gampi cannot be cultivated and is therefore rare and the most expensive of these three materials.

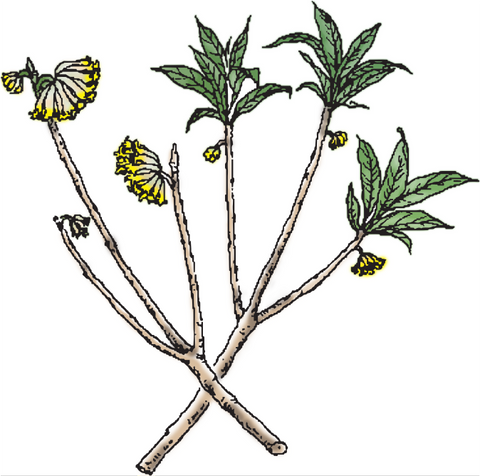

Mitsumata

(Edgeworthia)A bush that originated in China, Mitsumata grows to 1.0 - 1.5 meters in height. Records indicate that it was used in papermaking as early as 614. The fibers are shorter than Kozo's. Mitsumata papers have insect-repelling qualities.